This work, originally penned in 2009, stands as a snapshot of a world and a self that have since undergone profound transformation. Back then, I was a student grappling with the weight of history, my perspective shaped by the academic rigor and the historical context of that time. The world has shifted dramatically in the intervening years—nations, peoples, and global dynamics have evolved, and so have I.

My beliefs, my vision, and my sense of self have been reshaped by experience, reflection, and a deeper understanding of the complexities surrounding issues like the Armenian Genocide. This text, then, is a product of my younger mind—my “older cerebrum’s firmware,” if you will—a reflection of who I was and how I saw the world at that moment. It carries the passion and perspective of 2009, yet it remains a foundation for the ideas and insights that continue to evolve within me today.

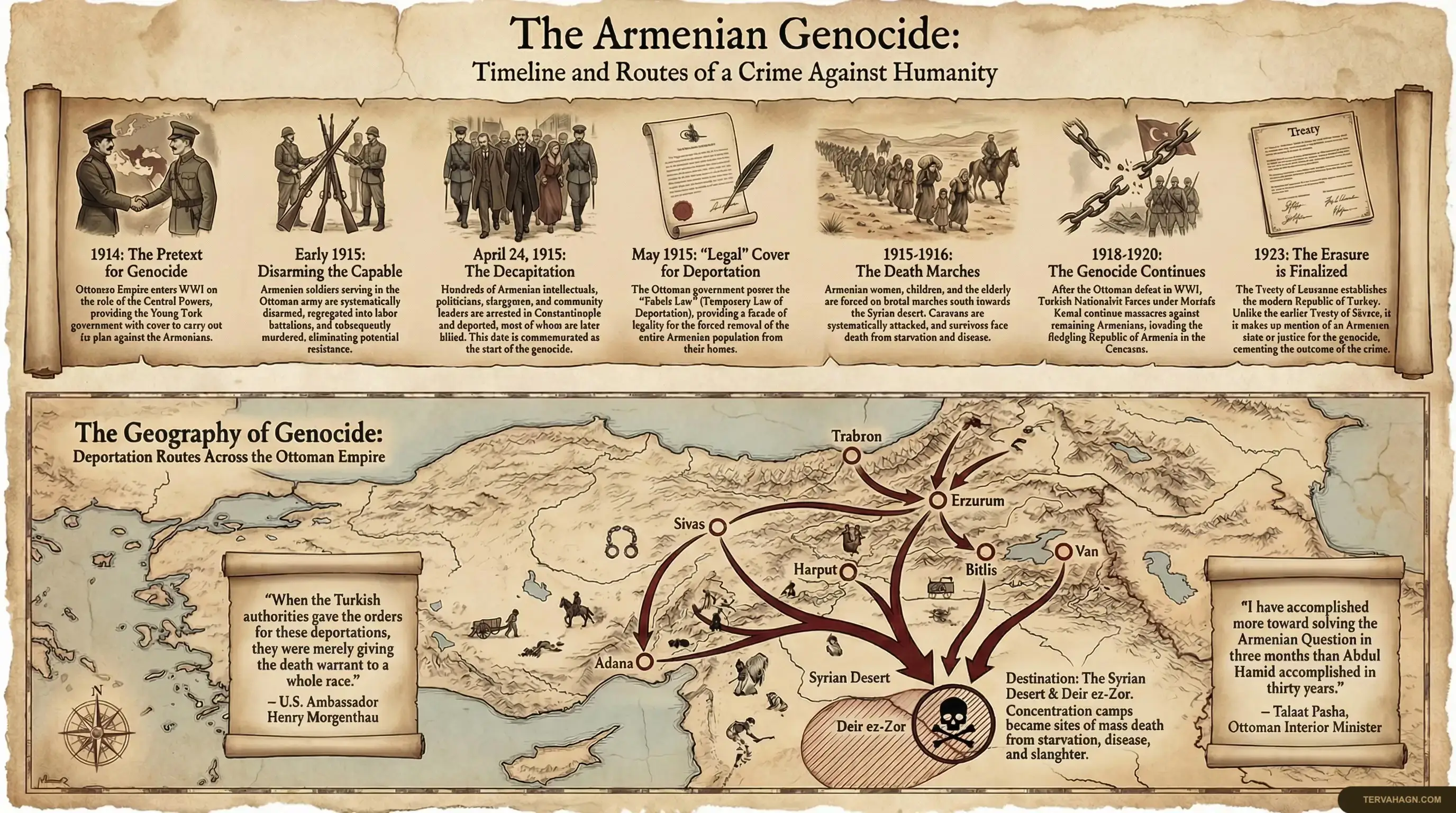

This thesis examines the historical events of the Armenian Genocide (1915–1923), the policies of the Ottoman Empire and the Young Turks, and the ongoing international effort to recognize and commemorate this tragedy.

International Recognition of the Armenian Genocide: Historical Analysis and Contemporary Issues

M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University Faculty of History Department of 19th – Early 20th Century Russian History

Diploma Thesis Completed by: V. A. Ter-Sarkisyan, Fifth-year student, International Relations Department Academic Advisor: O. G. Yumasheva, Cand. Hist. Sci. (Ph.D.), Senior Lecturer Moscow – 2009

The history of Armenia is dramatic. One would think it should not have survived and remained on the world’s political map. On the thorny roads of world history many mighty states have perished; yet Armenia stood firm, endured the tragic trials that befell its destiny, and did not submit to any foreign conqueror. Although it lost its independence for centuries at a time, it never ceased its struggle for freedom.

The Armenian Genocide in Ottoman Turkey was the first large-scale international crime in human history committed with the intent to destroy an entire people for political reasons. The deliberate actions of the Turkish government, documented by objectively verifiable facts and irrefutable documents and testimonies from a great variety of sources, fully meet the definition of the crime of genocide and fall under its definition in international law. To conceal from the world the physical extermination of one of the most ancient peoples, who had made a major contribution to human civilization, was an impossible task.

Turkey was the first country to recognize Armenia as an independent state after the collapse of the Soviet Union. But despite this fact and the years that have passed since then, diplomatic relations between the two countries have still not been established. The Turkish side refuses to open its borders or establish diplomatic relations with Armenia until Armenia seriously revises its stance on recognizing the territorial integrity and inviolability of the borders of the Republic of Turkey, and withdraws its accusations against Turkey and Turks of committing genocide against the Armenians during World War I.

The mass extermination of the Armenian population was the first instance of genocide in modern history and the first alarm bell. If the European states had heeded its ominous toll and promptly condemned this atrocity, there would have been no successors to the Turkish barbarians – namely, the German fascists. And Adolf Hitler in 1939 might not have declared at the infamous meeting with his top military commanders in Obersalzberg on the eve of the invasion of Poland: “I have given orders to my death squads to exterminate without mercy or pity all men, women, and children belonging to the Polish-speaking race.

Only in this way can we obtain the living space we need. After all, who remembers the annihilation of the Armenians today?”[1].

Today, nearly one hundred years after the mass extermination of the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire, the issue of the Armenian Genocide’s condemnation by the international community remains unresolved. However, in recent times there have been some shifts: resolutions condemning the Armenian Genocide have been adopted by a number of states, including Russia, France, Sweden, and Switzerland. Some Armenian organizations around the world are actively working toward this goal.

Facts have their own language. People must learn to read that language in order to draw lessons from their past. History shows that the past is full of mistakes, and one should neither deny them nor pin them on others. Far more important is to get to the roots and find the causes that led to the horrific events.

Throughout human history one can find many instances of genocide, from ancient times up to the present day. This is especially characteristic of wars of extermination and devastating invasions, conquerors’ campaigns, internal ethnic and religious conflicts, and the formation of colonial empires by European powers. However, it is worth separately examining the term “genocide,” the key concept guiding this work. Genocide is recognized as an international crime. In the Russian Federation, for example, Article 357 of the Criminal Code provides for criminal liability for genocide as a crime against the peace and security of humanity. The term “genocide” was first introduced in 1943 by Polish jurist of Jewish origin Raphael Lemkin, and it received international legal status after World War II, in December 1948, as a term defining the gravest crime against humanity. The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide was adopted and opened for signature and ratification by UN General Assembly Resolution 260 A(III) of December 9, 1948, and entered into force on January 12, 1951. According to Article II of the Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group as such:

• killing members of the group; • causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; • deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its

physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

Further, according to Article III of the Convention, the following acts are to be punished:

• genocide; • conspiracy to commit genocide; • direct and public incitement to commit genocide;

• attempt to commit genocide; • complicity in genocide.

Based on all the above, I will use the term “genocide” strictly in the legal sense, without any note of pathos or compassion, but objectively within the framework of generally accepted concepts.

One may read a thousand definitions of the concepts “task” and “goal” and still understand nothing without one banal phrase: the goal always lies beyond the scope of the activity. Everything we do consists of accomplishing certain tasks, and the result achieved is the goal. In other words, if a task is a means of achieving a goal or a detailed aspect of a goal, then in this work the goal lies in the issue of the international recognition of the Armenian Genocide. We face a number of tasks:

1. To analyze the facts of the genocide of the Armenian population in the Ottoman

Empire over the period from 1878 (the Treaty of San Stefano) to 1923 (the proclamation of the Turkish Republic). This is the subject of the first chapter of the thesis.

2. To examine the issue of the recognition of the genocide by the broadest strata of society – from ordinary citizens to the political elites of various states. This is the main part of the thesis, which is addressed in the second and third chapters. In those chapters, we have attempted to summarize all the most acute questions related to the international recognition of the Armenian Genocide.

New historical studies continue to appear on the Armenian Question, the genocide, and its international recognition. Historians of many countries are turning to what many had thought was the pain of one nation – which it is not. The issue is much broader and more important for history. The impunity of the Armenian Genocide had tragic consequences for the Jews who became victims of the Holocaust. Among the consequences of the impunity for this crime one can also include the escalation of acts of genocide in the modern world – the extermination of the population of the state of Biafra declared in January 1970, the mutual slaughter of the Hutu and Tutsi, the massacre of Serbs in Bosnia, the events in Kosovo, etc. All this, in the eyes of the international community, makes it urgent to raise anew the issue of Turkey’s responsibility for the crime it committed.

The most important source for the present work is considered to be the monumental work of Yuri G. Barsegov, “The Armenian Genocide: Turkey’s Responsibility and the Obligations of the World Community”[2]. Yuri Georgievich Barsegov was a Doctor of Law, professor of international law, author of a number of monographs and over 300 articles on various issues of international relations, diplomacy, and law, published in many countries around the world. The international recognition of Barsegov’s authority in international law was evidenced by his election by the UN General Assembly to the International Law

Commission (1987–1991), which is tasked with codifying and progressively developing international law.

Barsegov’s collection consists of documents containing the political and international legal evaluation of the actions of the Turks and Turkey by the international community – in the person of the Great Powers, the Paris Peace Conference, and the first worldwide political organization, the League of Nations – and their reactions in the form of assigning responsibility and taking measures of prevention or suppression and eliminating the consequences of the crime. The collection includes official documents reflecting the governmental viewpoint of individual countries — statements by heads of state and government, foreign ministers and other government representatives. It also includes materials of discussions of the Armenian Question in legislative bodies and their resolutions.

Particular attention is paid to documents of Russian origin – both those already in scholarly circulation and those uncovered in Russian archives which were restricted or closed in Soviet times. These documents mostly relate to the political history of the Armenian Question. Without studying them, it is impossible to understand what happened to the Treaty of Sèvres and the arbitral award of the U.S. President on the territorial delimitation between the Armenian and Turkish states. The Russian documents are also valuable in the context of the collection’s main theme – establishing the responsibility of the Turkish state for the Armenian Genocide and protecting the rights of the people who became the object of that crime. Documents of international bodies and organizations are of special value as they reflect the collective judgment of the international community.

The two-volume collection consists of seven sections. In the first section are documents containing general norms and principles of international law on the basis of which the responsibility of states and individuals for the crime of genocide is established. The second and third sections contain documents relating to establishing the responsibility of the specific Turkish state for the crime it committed – the genocide of the Armenians. The documents of the third section establish Turkey’s and the Turks’ responsibility for the genocide at the stage of the complete and widespread physical extermination of the Armenians in 1914–1923 in their historic homeland. The fourth section contains opinions of experts in international law and genocide, legal rulings and court judgments relating to the responsibility of the Turks and Turkey for the Armenian Genocide. The fifth section (volume 2) is devoted to the political history of the Armenian Question, including documents explaining why and through whose efforts the properly established responsibility was not realized. The sixth section contains documents reflecting the gradual process of the growing movement for reaffirming the fact of recognition of the genocide and realizing Turkey’s responsibility as an indispensable condition for drawing a final line under the past on the basis of international law.

The second most important source in our work is the collection by Professor M. G. Nersisyan[3]. This collection includes documents and materials from many sources – Armenian, Russian, Arabic, Turkish, German, English, French, American, and others – on

the Armenian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire. The majority of the documents are official reports, dispatches, and letters of consuls, ambassadors, ministers, high-ranking officials, and members and heads of governments of various countries, as well as testimonies of clergymen and missionaries about the mass slaughter of Armenians in Turkey. Being reliable documents of great value, they provide an accurate picture of the great tragedy of the Armenian people. Chronologically, the collection covers the period from 1876–1908 (the massacres under Sultan Abdul Hamid II) to 1909–1919 (the mass slaughter of Armenians under the Young Turks).

Also of interest is Armen Markarian’s “Russia and the Armenian Genocide of 1915– 1917”[4]. This collection of documents includes both materials already known to scholarship and little-known or entirely unknown documents concerning Russia’s policy on the Armenian Question during the genocide years (in the Armenian language). Chronologically, the documents cover the period 1915–1917, when three regimes succeeded each other in Russia: Tsarist, the Provisional Government, and Soviet. The documents are divided by year into three parts: groups of documents for 1915, 1916, and 1917. Thematically, the documents are divided into the following groups:

• Documents concerning the diplomatic correspondence of the Russian Ministry of

Foreign Affairs on the Armenian Question and regarding the genocide of the Armenian population in Turkey;

• Materials of the IV State Duma of Russia, in particular speeches by Armenian and Russian deputies on the plight of the Western Armenians and on the possibility of providing them all possible assistance;

• Decisions adopted by the three successive Russian governments on the Armenian

Question during the genocide years;

• Official documents of the Caucasian and Russian military authorities about the dire

situation of the Western Armenians;

• And aside from Russian sources, the collection contains French and American

documents concerning Russia’s policy on the Armenian Question.

The documentary work “1915: Irrefutable Evidence”[5] by the noted Austrian scholar Dr. Artem Ohandjanian represents a systematization and, in our view, an unbiased analysis of Austrian archival documents that shed light on the involvement of the Quadruple Alliance countries – especially Germany – in the preparation and implementation of the Armenian Genocide in the Ottoman Empire. Since 1982 the author has researched this issue; through his efforts, light has been shed on this atrocity, which has been characterized by international organizations as a crime against humanity and civilization.

An important source for our work is the first collection of Russian official sources on the Armenian Genocide, edited by G. A. Abrahamyan and T. G. Sevan-Khachatryan[6], which reflects not only advanced Russian thought – articles by public and political figures, and writers’ statements – but also documents from the State and Foreign Policy Archives

of Russia. The materials in the collection are presented chronologically and reflect the events of 1915–1916.

We should also note the collection of treaties edited by G. G. Azatyan[7], in which we find the key treaties of fateful significance for the Armenian people – from the Treaties of Gulistan (1813), Turkmenchay (1828), and Adrianople (1829) to the Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Mutual Assistance between the Russian Federation and the Republic of Armenia signed on August 29, 1997. Despite the nearly two-hundred-year span covered by the collection, it contains few documents, but all of them are of primary importance to us.

In Wolfgang Gust’s book “The Armenian Genocide (1915–1916)”[8], original official documents from the Political Archive of the German Foreign Ministry regarding the Armenian Genocide are presented. The book was the result of more than a decade of meticulous work by the author. It achieved great public resonance and became a powerful stimulus for serious discussions on the Armenian Genocide. The book clearly reveals not only the concern of various German consuls about the events, but also the reactions of official circles. Using dozens of documents, the author proves that Turkey used the pretext of war to completely annihilate the Armenians. It is noteworthy that Gust, who is not ethnically Armenian – and, as he admits, learned about and became involved with the Armenian Genocide issue completely by accident – said: “In 1992 I read a book in French describing the fate of a shepherd boy who barely escaped the slaughter. I was extremely surprised that this time it was not about a Jew, but an Armenian. That’s how I learned that before the Holocaust there was the Armenian Genocide.”[9]

For the main part of this work – the international recognition of the Armenian Genocide and contemporary issues in achieving recognition – we utilized both the aforementioned work of Yuri Barsegov and a large number of periodicals, the overwhelming majority of which were in electronic form. These include:

• Nezavisimaya Gazeta – one of the largest periodicals in modern Russia, devoted to

current problems of social, political, and cultural life in Russia and abroad (www.ng.ru);

• Golos Armenii – the Russian-language version of the most widely read newspaper in

Armenia (www.golos.am);

• The REGNUM Information Agency – a federal news agency disseminating news from

Russia and neighboring countries through its own correspondents, subsidiary agencies, and partners (www.regnum.ru);

• Lenta.ru – an online news publication (www.lenta.ru); • Moskovsky Komsomolets (MK) – the most popular Russian newspaper, published in all major cities of Russia, with daily updated articles, reviews, and commentary, and its own newswire (www.mk.ru);

• The Armenian National Institute (ANI) – a non-profit organization in Washington, D.C., USA. The institute’s primary mission is research and lobbying for the recognition of the Armenian Genocide. The institute’s website has published a large

number of documents from state archives around the world attesting to the Armenian Genocide, as well as evidence in the form of photographs, books, manuscripts and other artifacts from private collections and personal archives (www.armenian-genocide.org);

• RIA Novosti (Russian International News Agency) – a leading multimedia news

agency in Russia. Text, photographs, infographics, audio, video, animation, and cartoons – all these modern and traditional formats are widely used by the agency for timely coverage of events in Russia and abroad. The agency’s cutting-edge multimedia newsroom, launched in January 2008, has no analogue in Russia and embodies the most advanced technologies of news gathering, processing, and dissemination (www.rian.ru);

• BBC – the world’s largest broadcasting corporation (www.bbc.co.uk); • Day.Az – a national-scale information service in Azerbaijan, combining the functions of a daily newspaper, analytical journal, and news agency. It is one of the bestknown and most influential Azerbaijani online media outlets (www.day.az); • RosBusinessConsulting (RBC) – a news agency providing news feeds on politics, economics and finance, analytical materials, and thematic articles (www.rbc.ru).

The Armenian Question – a diplomatic term associated with the Armenian people’s struggle for liberation from Turkish domination, for self-determination and the right to establish their own statehood – entered common usage and became part of the Eastern Question after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 had special significance for the Armenian people, who sought liberation from the Turkish yoke and the freedom of both parts of Armenia under Russia’s protectorate. In January 1878 the Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople, Nerses Varzhapetyan, presented a document to the National Assembly outlining a program of Armenian self-government modeled on Lebanon (which since 1864 had been governed by a Christian governor). This program – likely dictated by the Turkish government and England (which preferred such a solution to the Russian occupation of Western Armenia) – was rejected. Under pressure from Armenian political circles in Constantinople and the Caucasus, which linked the liberation of the Western Armenians to Russia, the Patriarch of Constantinople, initially through his representatives and then personally, entered into contacts with the Russian command and diplomats and sent a petition to the Russian Emperor Alexander II. At the same time, on the initiative of Armenian public figure G. Artsruni, a petition was presented to the Viceroy of the Caucasus. The Russian government agreed to include a special clause regarding the Armenians in the RussoTurkish peace treaty. Thus Article 16 of the Treaty of San Stefano was born. For the first time, the Armenian Question received official recognition in a peace treaty – signed at San Stefano on March 3, 1878 – according to which the Sublime Porte undertook “…to carry out

without delay the improvements and reforms demanded by local needs in the provinces inhabited by Armenians, and to guarantee their security from Kurds and Circassians.”[35] Moreover, as stipulated by Article 25 of the treaty, Russian troops were to be withdrawn from Western Armenian territories only after six months, during which the Ottoman Empire had to fulfill its obligations under Article 16. Thus, Russia became the protector of the interests of the Armenian population. The Treaty of San Stefano guaranteed that the Sublime Porte would soon implement the necessary reforms to improve the lives of the Christian population of Western Armenia. It was from this time that the Armenian Question became a subject of discussion in international relations. However, the article could not fully satisfy the Armenians, since it said nothing about the much-desired autonomy.

This moderation of Article 16 is explained by the diplomatic pressure of England on Russia: the English government saw a threat to its interests in Asia and to the routes to India in Russia’s strengthened position. The Treaty of San Stefano greatly increased Russia’s influence in the Balkans and in Asia (by the acquisition of Batum, Kars, and other territories). It was precisely for this reason that the treaty was unacceptable to the European powers, especially England and Austria-Hungary, which led to a revision of the treaty at the 1878 Berlin Congress. As the newspaper Le France later aptly noted, despite the sincerity of some British statesmen, the London government always used the Armenian Question as a means to pressure the Sublime Porte: “Whenever the English government took a position in favor of the oppressed, without a doubt it was seeking its own benefit.”[36].

Striving to draw the attention of the European powers at the Berlin Congress to the situation of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, to place the Armenian Question on the agenda, and to secure the implementation by the Turkish government of the promised reforms under the San Stefano Treaty, Armenian political circles in Constantinople sent a national delegation headed by Mkrtich Khrimian to Berlin. However, they were not allowed to participate in the Congress. The delegation presented to the Congress a project for the self-governance of Western Armenia and a memorandum addressed to the Great Powers, which likewise were not taken into account.

The Armenian Question was discussed at the Berlin Congress in the sessions of July 4 and 6, 1878, amid a clash of two points of view: the Russian delegation insisted on implementing reforms before the withdrawal of Russian troops from Western Armenia, whereas the British delegation – relying on the Anglo-Russian agreement of May 30, 1878 (by which Russia agreed to return the Alashkert valley and Bayazet to Turkey) and on the secret Anglo-Turkish convention of June 4, 1878 (the Cyprus Convention), by which England undertook to oppose Russia by military means in the Armenian provinces – sought to avoid conditioning the reforms on the presence of Russian troops. In the end, the Berlin Congress adopted the English version of Article 16 of the San Stefano Treaty, which entered the Berlin Treaty as Article 61 in the following wording: “The Sublime Porte undertakes to carry out, without further delay, the improvements and reforms demanded by local needs in the provinces inhabited by Armenians, and to ensure their security from

Kurds and Circassians. It will periodically inform the Powers of the measures taken for this purpose, and the Powers will supervise their application.”[37]. This removed the one more or less real guarantee of implementing the Armenian reforms (the presence of Russian troops in the Armenian-inhabited areas) and replaced it with the unreal general guarantee of supervision of reforms by the Powers.

Under the Berlin Treaty, the Armenian Question was transformed from an internal issue of the Ottoman Empire into an international issue, becoming an object of the self-interested policies of imperialist states and world diplomacy – which had fateful consequences for the Armenian people. At the same time, the Berlin Congress was a turning point in the history of the Armenian Question and stimulated the Armenian national liberation movement in Turkey. In Armenian socio-political circles, disillusioned with European diplomacy, conviction grew that the liberation of Western Armenia from the Turkish yoke was possible only by means of armed struggle.

The situation of the Armenian people in Turkey, their struggle for liberation, the Armenian Question (which had arisen since the 1878 Berlin Congress), and the diplomatic maneuvers of the Powers around this issue – as well as the Armenian Genocide and its international recognition – have found broad reflection in Russian historiography. In Russian historical literature, there are few specialized works devoted solely to these issues, but they are covered in many works on the history of Russia, military history, and the history of international relations – especially in works on the Eastern Question and the history of Turkey – as well as in a number of published document collections.

The coverage of these issues took shape both in immediate reactions in the press of the time and in historians’ works published later. Historians’ positions vary, owing to their political convictions, but in the overwhelming majority of works a sympathetic attitude is expressed toward the tragic fate of the Armenian people, the policy of the Turkish ruling circles is sharply condemned, and the stance of the Western powers is likewise criticized. The pro-Russian orientation of the Armenian liberation movement and the assistance given to it by Russia are highlighted. In some works, there is also criticism of the Tsarist policy at certain stages of the Armenian Question, when inconsistency and retreat by Tsarist diplomacy from the defense of Armenian interests became evident due to the international situation.

In many works by Russian historians, there are interesting data, facts, and observations related to the 1877–78 Russo-Turkish War, the 1878 Berlin Congress, the emergence of the Armenian Question, and the intensification of contradictions among the Western powers over the Armenian Question in the late 19th – early 20th centuries.

In the works of Russian military historians – F. I. Bulgakov (“The Heroic Defense of Bayazet”), G. K. Gradovsky (“The War in Asia Minor in 1877”), M. V. Alekseyev (“The War of

1877–1878 in the Asian Theater”), P. Garkovenko (“Russia’s War with Turkey”), P. I. Averyanov (“A Brief Military Survey of the Caucasus-Turkish Theater of Operations”) – the participation of Armenians in that war on Russia’s side is described: their pro-Russian orientation, the help of the Armenian population to the Russian troops, and the role of Armenian generals in the Russian army (Loris-Melikov, Ter-Ghukasov, Lazarev, Shelkovnikov, and others) in operations on the Caucasian front. Particularly much attention to these matters was devoted in the works of V. Potto (“The First Volunteers of Karabakh”; “The Caucasian War”; “The Kars Celebrations of 1910 and the Four Sieges of Kars”; “General-Adjutant Ivan Davidovich Lazarev”).

In books published after the war and the Berlin Congress (V. A. Abaza’s “History of Armenia”; N. R. Ovsyanny’s “Modern Turkey”; the collection “The Peoples of Turkey”), the dire situation of the Armenians in Turkey during and after the war is shown, as well as the intensification of oppression and violence by the Turkish authorities. The sharp deterioration of the Armenians’ condition in Turkey after the Berlin Congress and the mass massacres of 1894–1896 (which marked the beginning of Turkey’s genocidal policy) aroused a powerful wave of protest in Russia and a public movement to defend the Armenians’ rights – something reflected in historical literature.

Progressive Russian public figures organized in Moscow the publication of two compilations – “The Condition of Armenians in Turkey Before the Intervention of the Powers in 1895” and “Brotherly Aid to Armenians Suffering in Turkey”. In the latter, in a show of solidarity with the Armenians and to support the public movement in Russia to aid the Armenians, many prominent historians participated – M. Kovalevsky, P. Milyukov, V. Potto, M. V. Nikolsky, R. Shtakelberg, P. I. Belyaev, L. A. Kamarovsky, and many others. Some of the articles in these volumes directly concern the Armenian Question. The most interesting is L. A. Kamarovsky’s article “On Reforms in Turkey”, whose author had long been interested in the Armenians’ fate. Back in 1889 he sent a letter to the editor of the Armenian newspaper Hayastan published in London, in which he condemned the policy of the Powers, including Russia’s, regarding the Armenian Question. In L. Kamarovsky’s article “On Reforms in Turkey,” he discusses Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s policy and the massacres of Armenians, and raises the question of the necessity of intervention by the Powers. The author also addresses these issues in his book “The Eastern Question.”

In other works by a number of Russian historians published in the late 19th century (S. A. Zhigarev’s “Russia’s Policy in the Eastern Question”; K. Skalkovsky’s “Russia’s Foreign Policy and the Position of Foreign Powers”; V. Tenishev’s “The Shame of Civilization: On the Turkish Affairs”; V. T. Mayevsky’s “Van Vilayet: A Military-Statistical Description”), the events of 1894–1896 in Turkey – the mass massacres of Armenians, the policies of the Powers on the Armenian Question after the Berlin Congress, the failure to implement those decisions, and the lack of practical aid to the Armenians from the Powers – are also covered.

In Russian historical literature of the early 20th century and the eve of World War I, during the formation of new alliances in Europe, such issues were reflected as the rise to power of

the Young Turks in 1908 and their policy toward the Armenian population; the intensification of Russia’s policy, in particular toward Turkey (Russia’s initiative and sustained efforts to implement reforms in Western Armenia in 1912–1914); and the renewed heightened interest in Russia in the fate of the Armenians associated with all these events.

In the works of I. I. Goluboyko (“Old and New Turkey”; “Turkey”), events associated with the massacres of Armenians in Sasun and other places are illuminated. Statistical data are given on the enormous number of victims and the destruction during the massacres of 1894–1896; the dire condition of the Armenians in Turkey under the Young Turk regime is shown; and their policy toward Turkey’s non-Muslim minorities is analyzed. These issues are also covered in articles by V. Vodovozov, A. Kaufman, and others published in the Turkish Compendium, as well as in works by historians S. Goryainov (“The Bosporus and the Dardanelles”), I. R. Bazhenov (“Our Foreign Policy in the Near East from a National Perspective”), and M. Mikhailov (“The Bloody Sultan”), and so on.

The events of World War I – the mass genocide of the Armenians in Turkey and the usurpation of their historic homeland (Western Armenia); the dispersal of the Armenians across the world; the policies of the Powers toward Armenia during the war; the Armenian volunteer movement – all these issues, naturally, could not immediately become the subject of thorough research, and so in Russian historiography of that time there are virtually no works devoted specifically to these questions.

Russian historians’ attitudes toward these events were expressed mainly in their articles in the press, as immediate responses to the tragic events – which in turn had sparked a new progressive movement in Russia in defense of the life and rights of the Armenian people.

During the war, to aid Armenian refugees and inform the Russian public about the Armenians’ fate, a weekly “Armenian Herald” was launched in Moscow and a monthly journal “Armenia and the War” in Odessa. Many prominent figures of the Russian intelligentsia and public life raised their voices in the press in defense of the Armenians. In the pages of Armenian Herald, articles appeared by P. Burski (a series “On the RussoTurkish Front”), Prince P. D. Dolgorukov (“The Armenian Question and Russian Society”), V. Obninsky (“On the Path to Revival”), and others. Also noteworthy is F. Zabludovsky’s article “France and the Armenian Question,” published in the journal Armenia and the War.

Of significant interest is the article by Academician B. A. Turaev “Russia and the Christian East”, published in issue 3 of the collection “Russia and Her Allies in the Struggle for Civilization” in 1916, in which the author acquaints the reader with the history and culture of Armenia and Russo-Armenian ties, recounts the Russo-Turkish wars and the participation of Armenians in them, and writes about the San Stefano Treaty and the 1878 Berlin Treaty – noting that Article 61 gave “the Porte the signal for systematic massacre and extermination”[38] of the Armenian people – and emphasizes the importance of the liberation of Western Armenia and the preservation of its historical monuments for Russian historical science.

Fundamental works on the history of the Armenian Question and the Armenian Genocide in Turkey were written by the Russian diplomat, historian, and jurist A. I. Mandelstam. In his book “The Young Turk State” and especially in “The Fate of the Ottoman Empire”, he highlighted Turkey’s policy toward the Armenians, providing detailed information on the events leading up to the Genocide of 1915 – on the deportations, violence, and massacres carried out against the Armenians during World War I. In another work – “The League of Nations and the Great Powers vis-à-vis the Armenian Question” – Mandelstam presented the most thorough history of the Armenian Question in pre-Soviet Russian historiography, from the 1856 Treaty of Paris up to the 1923 Lausanne Conference. Notwithstanding certain methodological shortcomings, one cannot fail to appreciate the extensive factual material contained in this work, which illuminates the policies of Turkey and the Powers regarding the Armenian Question. The book extensively covers the issue of reforms in Western Armenia in 1912–1914, and analyzes Russia’s policy in defense of Turkey’s Armenian population. The history of the 1915 genocide is described in detail, with valuable documents presented that particularly illustrate Kaiser Germany’s responsibility in the extermination of the Armenians.

P. N. Milyukov also addressed the Armenian Question in his works. In a number of writings (“The Balkan Crisis and A. P. Izvolsky’s Policy”; “The History of the Second Russian Revolution”, etc.), Milyukov – while sympathetic to the Armenians’ plight in Turkey and noting “the loyalty of the Armenians to Russia” – nevertheless not only failed to support the idea of creating an independent Armenian state, but was even against Armenia’s autonomy. He acknowledged only the need for uniting the Armenians within the Russian state, and viewed Armenia as an important element of Russian policy in the East. He believed that primary responsibility for the fate of the Armenians in Turkey lay above all with England.

In the works of F. A. Rotshtein[22] (“International Relations at the End of the 19th Century”; “The Seizure and Enslavement of Egypt”; relevant chapters of “A History of Diplomacy”; and a number of articles), many issues are examined relating to the policy of the European Powers at the end of the 19th century toward the fate of the Armenian people. Noting the self-interested aims of the Europeans – particularly British diplomacy – Rotshtein arrives at the just conclusion that as a result of the sharp rivalries among the European Powers, the implementation of Article 61 of the Berlin Treaty (on reforms in Turkish Armenia) was effectively left to Turkey’s discretion, and the interests of the Armenian people were forgotten.

Considerable attention to the Armenian Question – in particular to Kaiser Germany’s policy – was paid by A. S. Yerusalimsky[23] in his work “Foreign Policy and Diplomacy of German Imperialism at the End of the 19th Century.” This book extensively illuminates the bloody policy of Sultan Abdul Hamid II and the massacres of Armenians in 1894–1896 in Turkey, showing that European public opinion demanded measures “to save the muchsuffering Armenian people, but the governments of the Great Powers did not hesitate to use the fate of the Armenians as one of the items of shameful diplomatic bargaining”[24]. In this monograph, drawing on archival documents, the hypocrisy of

German diplomacy is exposed, and the true role of the German government is shown – as accomplice and patron in carrying out the bloody plans to exterminate the Armenians in Turkey.

United States. American historical scholarship turned to the Armenian Question in the 1890s, particularly beginning with the massacres and massacres of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1894–1896. In many leading U.S. newspapers of the time, numerous articles and reports were published about the life of the Ottoman Armenians, the policy of the Sultan’s government toward the Armenian population, the positions of the European Powers on the Armenian Question, and eyewitness testimonies – by American missionaries, diplomats, and Armenian refugees from Turkey.

A vast amount of factual material on the condition of the Western Armenians – concrete data and truthful accounts of the massacres – is contained in works by American authors such as John O’Shea (“The Curse of Armenia”), T. Peterson (“Turkey and the Armenian Crisis”), J. McDermott (“The Great Assassin and the Christians of Armenia”), G. Givernat (“Armenia: Past and Present”), and D. Gregory (“The Crime of Christendom: The Armenian Crisis and Massacres”), and G. Tupper (“Armenia: The Present Crisis and Past History”).

Valuable sources for studying the history of the Ottoman Empire, Western Armenia, the policies of the European Powers and the USA regarding the Armenian Question, and the massacres of 1894–1896 are studies by American missionaries: E. Bliss (“Turkey and the Armenian Atrocities”), S. Hamlin (“The Armenian Massacres”; “The Martyrdom of an Nation”; “The Genesis and Evolution of the Policy of Turkish Massacres of Armenian Subjects”), F. Greene (“The Armenian Crisis in Turkey: The Massacres of 1894”; “The Armenian Massacres”), as well as works by journalists L. Abbott (“The Armenian Question”), and E. Godkin (“The Armenian Troubles”; “The Armenian Atrocities”).

The books of Henry G. Gibbons (“Armenia in the World War”; “The Blackest Page of Modern History: The Events in Armenia in 1915”) are based on authentic documents and reliable facts; their sources included reports of the American Committee for Relief in Armenia and Syria, letters of German missionaries, and numerous eyewitness testimonies published in various American and British newspapers.

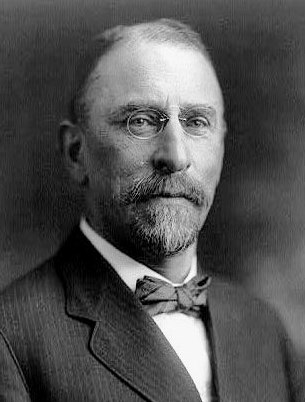

An important source on the Armenian Genocide problem are the works of U.S. Ambassador to Turkey Henry Morgenthau: “The Tragedy of Armenia” and “On the Armenian Massacres.” In 1926, Ambassador Morgenthau’s Story (his memoirs) was published in New York, in which, among other things, he recounted his conversations with Talaat and other Young Turk leaders. The chapters devoted to the deportation of the Armenians and their extermination in the deserts of Mesopotamia were based on reports of the American Consul in Aleppo.

In the United States, specialized studies on the Armenian Genocide have been published that draw on a wealth of factual material: e.g., T. Boyajian’s “Armenia: The Case of the

Forgotten Genocide,” G. Partchajian’s “Hitler and the Armenian Genocide” and “The Armenian Genocide in Perspective,” and J. Nazer’s “The First Genocide of the 20th Century.”

In 1980, R. Kloian published a compendium “The Armenian Genocide,” a collection of facsimiles of several hundred reports and articles on the Armenian Genocide that were published in various U.S. newspapers and journals from 1913 to 1922. Richard Hovannisian compiled a comprehensive bibliographic index “The Armenian Massacres,” listing archives of various countries where documents on the genocide are kept, as well as the main foreign publications on the subject. The theoretical aspects of genocide, and of the Armenian Genocide in particular, are the subject of studies by V. Dadrian (“Common Features of the Armenian and Jewish Genocides”; “Methodological Components of the Study of Genocide”; “Structural-Functional Components of Genocide”).

The campaign by the Turkish authorities and Turkish historical scholarship to falsify history and discredit the issue of the Armenian Genocide has gained support from certain American political scientists and historians. Examples of tendentious – even outright falsified – portrayals of historical events include works like Stanford J. Shaw’s “History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey” and K. Karpat’s “The Politics of Turkey”. In 1986 the Turkish-American Association in Washington published “The Armenian Allegation: Myth and Reality,” with a foreword by Turkey’s U.S. ambassador Şükrü Elekdağ, which is a compendium of tendentious anti-Armenian materials that distort the history of the Armenian Question.

Great Britain. The issues of the political history of the Armenian people and the Armenian Question came to be reflected in British historiography starting mainly in the 1870s. The dire condition of the Western Armenians under the Sultan’s rule, the intensification of persecution and oppression of Armenians by the Turkish authorities in the 1870s–1880s, and the manifestations of the Armenian national liberation struggle are examined in works by British authors such as W. Dutton (“The Christians of Turkey: Their Condition Under Moslem Rule”), J. Farley (“The Turks and Christians: The Solution of the Eastern Question”), J. Probyn (“Armenia and Lebanon”), G. Sandworth (“How the Turks Rule Armenia”), J. Smith (“Armenia Under Turkish Rule”), and W. Ramsay (or Railey) (“Christians and Kurds in Eastern Turkey”), among many others.

In the studies of S. Norman (“Armenia and the Campaign of 1877–1878”), F. Greene (“The Russian Army and Its Campaigns in 1877–1878”), and C. Williams (“The Armenian Campaign: A Diary of the Campaign of 1878 in Armenia and Kurdistan”), issues are illuminated relating to the condition of the Western Armenians during the 1877–1878 Russo-Turkish War, military operations in Western Armenia, the assistance of the Armenian population to the Russian army, and so on.

The diplomatic rivalry of the Powers over the Armenian Question, and the results of its discussion at San Stefano and Berlin in 1878, are analyzed in the works of M. MacColl

(“The Eastern Question: Facts and Fictions”), S. Abgar (“The Armenians and the Eastern Question”), the Duke of Argyll (“The Eastern Question from the Treaty of Paris 1856 to the Berlin Treaty 1878”), James Bryce (“The Future of Asiatic Turkey”), I. Whittaker (“The Prospects of Asiatic Turkey”), T. Holland (“The European Concert in the Eastern Question”), and M. Swasie (“The Armenian Question”). These works reflect the British public’s concern for the fate of the Ottoman Armenians and offer judgments and proposals regarding the future arrangement of Western Armenia, the necessity of implementing reforms to improve the Christian population’s conditions, and the fulfillment by the Powers of their obligations under the 1878 Berlin Treaty.

The intensification of Abdul Hamid II’s anti-Armenian policies – the organization by the Sultan’s government of the 1894–1896 massacres of the Armenian population – received broad reflection in British historiography. During the 1890s and 1900s, over 100 books and articles on the Armenian Question were published in Great Britain. The situation of the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire, descriptions of the massacres of the 1890s, and the Armenian national liberation movement are addressed in works of the aforementioned James Bryce (“Transcaucasia and Ararat”), R. Davey (“Turkey and Armenia”; “The Sultan and His Subjects”), E. Dillon (“Armenia and the Armenian People”; “The Condition of the Armenians”), as well as in works by Gladstone, E. Guinness, Claude H. Conder (Hodgetts), M. MacColl, W. Ramsay, and many others.

Some British authors advocated for the complete partition of the Ottoman Empire among the Great Powers or for the creation of several independent states in its place – including an independent Armenia. Others opposed coercive measures against the Sultan and instead demanded the implementation of reforms under the Powers’ supervision. James Bryce, I. Hodgetts, and M. MacColl believed that the only salvation for Turkey’s Armenian population was military intervention by Great Britain, supported by the other European powers.

A vast body of factual material on the Armenian Question is contained in collections of British diplomatic documents published in the 1890s by the Foreign Office, as well as in editorial articles in British journals like The Spectator, The Contemporary Review, and The Fortnightly Review.

Issues concerning the condition of the Armenian population of Turkey on the eve of World War I – the internal policy of the Young Turk government, the massacres in Adana in 1909, the discussion of reforms in Western Armenia in 1912–1914, and the Powers’ policies on the Armenian Question at this new stage – are covered in the articles and books of E. Pears (“Turkey and Its Peoples”; “Turkey and the War”), F. Cavendish (“Danger in Armenia”), E. Robinson (“The Truth about Armenia”), E. Ferriman (“The Young Turks and the Truth about the Adana Massacre of April 1909”), M. Price (“The Problem of Asiatic Turkey”), and F. Sketchley (“The Armenian Question”).

Many British authors warned their government of the threat of physical annihilation hanging over the Armenian population of Turkey on the eve of the world war. World War I and the Armenian Genocide in Turkey stimulated increased interest in the Armenian

Question in British historiography. Valuable publications of documentary materials appeared about the situation of the Armenian population in Turkey during the war, the genocide and deportation of the Western Armenians. Notably, these include document collections compiled by James Bryce (“The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire, 1915–1916”), Arnold Toynbee (“Documents on the Treatment of Armenians and Assyrian Christians in the Ottoman Empire and Northwestern Persia”), and Aram Andonian (“The Memoirs of Naim Bey”).

A wealth of factual material and testimony about the reactionary domestic policy of the Young Turk government, the genocide and deportation of the Armenians, and the plight of refugees in various countries is contained in works by A. Safrastian (“The Current Situation in Armenia”), E. Robinson (“Armenia and the Armenians”; “The Condition of Our Ally Armenia”), Arnold Toynbee (“Armenian Atrocities: The Murder of a Nation”; “The Murderous Tyranny of the Turks”), W. Williams (“The Tragic History of Armenia”), L. Chambers (“The Massacres of Armenia”), J. Douglas (“The Death Road in Anatolia and Armenia”), and L. Einstein (“The Armenian Massacres”).

The policies of Great Britain and other powers toward Armenia, and discussions of the Armenian Question in the British Government and Parliament and at postwar international conferences, are the subject of works by the aforementioned James Bryce (“The Future of Armenia”; “The Settlement of the Near East”), G. Buxton (“Armenia and the Settlement”), S. Lees (“Armenia and the Allies”), I. Pitt (Pittling) (“The Armenian Question in the House of Commons”), J. Marriott (“The Eastern Question in European Diplomacy”), G. Mikhaelyan (“The Future of the Armenians”), R. Roade (“Armenia: British Commitments and the Near East”), and A. Safrastian (“Germany and Armenia”).

From the 1920s to the present, English historians have studied a wide range of issues related to the history of the Armenian Question from 1878 to 1923 – in particular, Great Britain’s and other powers’ policies toward Western Armenia; the Turkish government’s anti-Armenian policy; the discussions of the Armenian Question at postwar conferences; as well as the questions of the dispersion of Armenians (deportees) to countries of the Near East, Europe, and the Americas; the life of Armenian communities; and the revival of the Armenian Question in 1944–1946. These and other problems of the political history of the Armenian people are examined in the studies of I. Paye (“The Armenian Problem”), J. Barton (“The Dispersion of the Armenians”), G. Woods (“The Armenians Yesterday and Today”), P. Shaw (“The European Powers and the Near Eastern Question”), D. Lang (“The Armenians”; “Armenia: Cradle of Civilization”; “The Armenians: A People in Exile”), and many others.

In the works of this latest period, significant documentary material contained in the archives of Great Britain and other countries has been utilized. In discussing the Armenian Question and the Armenian Genocide – as well as its international recognition – these historians also provide information on Armenia’s history and culture, and note the contribution of the Armenian people to the development of world civilization.

France. Public opinion in France was among the first to protest and condemn the antiArmenian policy of Sultan Abdul Hamid and the Young Turk rulers. From 1900 through the 1980s, over 400 books, document collections, and articles devoted to the history of the Armenian Question were published in France; the same issue was reflected in numerous articles in socio-political and scholarly periodicals. The immediate responses to the events in Turkey in the late 19th and early 20th centuries – the deportations and massacres of the Armenian population – were the works published on the eve of and during World War I by French historians, journalists, and some eyewitnesses.

A certain contribution to the historiography of the problem was made by the works of A. Adossidès (“The Armenians and the Young Turks: The Cilician Massacre”), René Pinon (“The Extermination of the Armenians: A German Method, a Turkish Work”), and Jacques de Morgan (“Against the Barbarians of the East”). A significant portion of these works is descriptive; the authors relate the dire condition of the Armenians in their ancestral homeland (Western Armenia) and their cruel oppression, without delving into an analysis of the socio-economic and political causes. An anti-German tendency predominates – an effort to show that Imperial Germany, as Turkey’s ally, was an accomplice in the crime. Some authors, such as Pierre Loti and Claude Farrère, supported the official Turkish version of an allegedly “general Armenian uprising,” trying to cast the blame for what happened on the victims themselves.

The works of the 1960s–1980s are of the greatest value, in which a comprehensive, objective assessment of Turkey’s genocidal policy is given. These issues are thoroughly covered in the works of Jean-Marie Carzou (“Armenia 1915: An Exemplary Genocide”) and Yves Ternon (“The Armenians: History of a Genocide” and “The Armenian Question”). Ternon notes that the massacre of Turkey’s Armenians in 1915 was the first genocide of the 20th century – the first collective murder carried out according to a premeditated plan and with modern means at the disposal of a totalitarian state. Among the motivating causes of the Armenian Genocide, Turkish nationalism, chauvinism, and Pan-Turkism are highlighted. With the disappearance of the Armenians, an obstacle standing in the way of Pan-Turkism in the Ottoman Empire (and simultaneously of a Pan-Turkism aiming to unite the Turks of the Ottoman and Russian Empires) was removed.

A number of authors, examining the causes of the Armenian Genocide, conclude that at the root of the Young Turks’ anti-Armenian policy lay not religion but race – the desire for the domination of the exclusively Turkish race. It was the racial idea, not the defense of Islam, that was the main cause of the massacres; the defense of Islam played a secondary role. This view is held by Léon and Aram Shabri. Some authors emphasize Hitler’s use of the “Armenian precedent” when he carried out the genocide of the Jews, Slavs, and Roma. “The slaughter of the Armenians at the dawn of the 20th century was the dress rehearsal for those mass killings which soon would be elevated to the status of an art of governance,” wrote E. de la Souchère in his book “Racism in a Thousand Images” (1967, p. 217).

French literature of this period also portrayed the heroic self-defense by the Armenians of Sasun, Van, Shapin-Garahisar, Urfa, and on Mount Musa. The French public was moved by accounts of Armenian resistance against overwhelming odds during the massacres.

Particularly valuable are the works that provide a fully documented, balanced assessment of the Armenian Genocide. These include Jean-Marie Carzou’s and Yves Ternon’s studies, which firmly established in Western scholarship that the 1915 slaughter of the Armenians constituted genocide. Ternon emphasizes that the Young Turks’ crimes were driven by extreme nationalist and Pan-Turkic ideology: by eliminating the Armenians, the Young Turks believed they were removing an obstacle to unifying all Turkic peoples from the Ottoman Empire to Central Asia.

Many French authors also note the link between the Armenian Genocide and the subsequent Holocaust. They argue, for example, that Hitler was emboldened by the world’s indifference to the Armenians’ fate – encapsulated in his infamous remark about who remembered the Armenians – and that the impunity enjoyed by the Young Turks provided a dangerous example. In the words of one French author, “The massacres of the Armenians at the dawn of the 20th century were a dress rehearsal for the mass murders later elevated to an art by those in power.”

German Historiography

German historiography turned to the Armenian Question at the end of the 19th century, in connection with the massacres of Armenians in Turkey in 1894–96. In 1896 the humanist and public figure Johannes Lepsius published “Armenia and Europe: Accusations Against the Great Christian Powers and an Appeal to Christian Germany,” which was based on a series of his articles collectively entitled “The Truth about Armenia” published in the German press. The materials presented by Lepsius convincingly demonstrated that Turkish military and civil authorities took direct part in the slaughter of Armenians, in pillaging, and in the forcible conversion of Christians to Islam. Lepsius exposed the Turkish authorities’ efforts to conceal their crime, revealing a deliberate mechanism devised by the Turkish ruling circles to pin the blame on the Armenians in case news of the massacres in the Ottoman Empire leaked out to Europe. The author refuted another thesis of the Turkish interpretation of events – the claim of the Turkish authorities’ “inability” to stop the massacres. He showed that the perpetrators understood perfectly well that they were acting in the name of and by order of the Sultan, that guarantees of their impunity issued from the highest authorities and not merely from local officials. After examining the policy of the Great Powers on the Armenian Question, Lepsius concluded that after signing the 1878 Berlin Treaty, they took no measures to carry its terms into effect, and the Armenian people became the victim of the Great Powers’ hypocritical policies in the years leading up to the tragic events. In 1916 another work by Lepsius was published, “Report on the Situation of the Armenian People in Turkey,” which incorporated testimony collected during the author’s trip to Constantinople in 1915 from German employees and

missionaries, diplomatic representatives of neutral countries, and other information reconstructing the picture of the Armenian Genocide and revealing the true purpose of the deportations – the extermination of the Armenian people. The total number of Armenians killed and deported was estimated by Lepsius at 1,396,350 people. Considerable attention was devoted to refuting the official Turkish claims of an “Armenian uprising” and “treachery” by Ottoman Armenians. Lepsius stressed that the organized self-defense by Armenians in certain places was a lawful measure of self-protection in the face of massacres of the civilian population. Turning to the issue of responsibility for the genocide and deportations, he asserted that for the deportation order, the methods of its execution, the massacres and violence, the responsibility rested with the Turkish government. The deportation of 1.5 million Armenians from various parts of the empire could not be justified on military grounds. J. Lepsius was the first in Europe to connect the bloody events in the Ottoman Empire with the ideology of Pan-Turkism. In 1919 the Report was reissued – with important additions and under the subtitle “The Extermination of the Armenian People.”

One of the first testimonies by a German eyewitness to the massacres was the appeal of Martin Niepage, who from 1912–16 was a teacher at the German technical school in Aleppo – “A Few Words to the Official Representatives of the German People.” Previously published in French and English, this appeal exposed the Young Turks’ crimes and blamed Germany for its policy on the Armenian Question.

In the work of the orientalist Joseph Markwart “The Rise and Rebirth of the Armenian Nation,” it was concluded that the Ottoman government viewed the approach of world war as the most favorable moment to carry out its long-contemplated plan to exterminate the Armenians, and that the main slogan of Turkey’s ruling circles, even after the constitution was proclaimed, remained: “When there are no Armenians, there will be no Armenian Question.” The author noted that the Young Turks in their brutality yielded in nothing to Abdul Hamid. Markwart strongly condemned the German government, general staff, and press, which, in his view, were also responsible for the Armenian Genocide.

A significant contribution to the study of the history of the Armenian Genocide is Heinrich Vierbücher’s work “Armenia 1915: What the Kaiser’s Government Concealed from the German People – The Massacre of a Civilized Nation by the Turks.” The author – a public activist, participant in the pacifist movement, and anti-fascist who worked in the Ottoman Empire during World War I – examines a broad range of issues related to the Armenian Question. He discusses the question of Germany’s responsibility, provides a historical overview of the military-political and economic relations between Germany and Turkey, and traces the continuity of the policies of Sultan Abdul Hamid and the Young Turks. The work draws on documents published by J. Lepsius and other materials that reveal the picture of the Armenians’ extermination. Vierbücher compellingly argues that the atrocities against the Armenian people were deliberate and planned. He lays bare the essence of Pan-Turkist aspirations and the policies of the Committee of Union and Progress, even titling one chapter of his work “Turkish Imperialism.” Discussing the 1915 deportations, the author states that this measure was in fact a premeditated murder. The work ends with a chapter “A Deceived People,” in which the author notes that “the new dictator Kemal

Pasha was a worthy follower of Talaat and Enver” (p. 79). G. Vierbücher believes that the Treaty of Lausanne was for the Armenians “the collapse of all hopes,” and he observes that if the League of Nations failed anywhere, it was precisely on this issue.

The coming to power of fascism in Germany, World War II, and the crushing defeat of the Third Reich spurred comparisons between the Holocaust and the earlier Armenian Genocide. German scholars of the post-war period, freed from wartime censorship and guilt, began to re-examine their own country’s role in the Armenian Genocide. It became increasingly acknowledged in German historiography that Imperial Germany, as the Ottoman Empire’s wartime ally, bore a share of responsibility – through complicity or willful blindness – for the genocide of 1915.

One notable post-war development was the publication of key German diplomatic archives concerning the Armenian Genocide. In 1919, Lepsius had already published “Germany and Armenia: 1914–1918,” a collection of secret German diplomatic documents that demonstrated the German authorities’ full knowledge of the Young Turks’ murderous intent and methods. Much later, in 2005, Wolfgang Gust published a comprehensive collection of German Foreign Office documents on the Armenian Genocide (translated into English in 2014), further substantiating the genocidal intent and execution as seen by Germany’s own representatives.

By the 1980s, German scholars like Hilmar Kaiser and Tessa Hofmann also contributed important research on the genocide, analyzing German responsibilities and the coverage of the genocide in German media and scholarship. The recognition by the German Bundestag in 2016 of the German Empire’s complicity in the Armenian Genocide marked a culmination of this historiographical trend in acknowledging historical truth and responsibility.

Turkey. Turkish historiography’s literature on the Armenian Question evolved significantly. Works published during the final phase of World War I and immediately thereafter were not genuine historical research, but rather collections of documents aiming to justify the wartime mass deportation of the Armenian population. At that time, the Turkish ruling circles did not yet feel a need to deny the genocide – especially since it was still ongoing – but rather sought to convincingly justify the deportation. As early as 1916, a booklet “The Goals and Revolutionary Activities of the Armenian Committees” was published in Constantinople, which advanced the idea of an allegedly impending general Armenian armed uprising against the Turkish state. This booklet, published at the initiative of the Turkish Ministry of the Interior, was the first serious attempt to falsify the recent events, and the concept it expressed took hold in Turkish historiography for a long time.

Towards the end of World War I, when Turkey’s defeat became evident and the prospect arose of having to answer for its crimes, the task of interpreting historical events was taken up by the War Ministry and the General Staff of the Turkish army. There arose a need to find a justification for the extermination of the Armenians – which was impossible to outright

deny. A new narrative emerged of “mutual massacres” and “atrocities committed by Armenians,” which also entered Turkish historiography. Among the first works of this kind were compilations such as “Documents on the Atrocities Committed Against the Muslim Population” (translated into French and published in 1919 under the title “Documents on the Atrocities Committed by the Armenians Against the Muslims”), “The Turkish-Armenian Question: The Turkish Point of View” (in English), “Operations of the First Caucasian Corps in 1918 and Their Witnesses”, “The Atrocities Committed by Armenians Against the Muslims of Transcaucasia in July 1919”, “The League of Nations and the Greeks and Armenians in Turkey” (in English), and many others. The tendentiously selected documents and materials in these collections depicted the Turks as victims of the Armenians; at best it was conceded that the massacres (the term “genocide” was not used then) were of a reciprocal nature.

To this group of Turkish literature can be added the memoirs of the direct organizers of the Armenian Genocide: Talaat Pasha’s “Memoirs”, Cemal Pasha’s “Memoirs”, the CUP party secretary Şükrü Bleda’s “The Collapse of the Empire”, as well as the historian Ahmed Refik’s “On the Roads of the Caucasus.” The authors of these works do not deny the fact of the mass killings of Armenians, but they dispute the organized, intentional character of this crime. They portray events as if the Armenians, with the help of Turkey’s enemies (primarily Russia), were preparing to destroy the Turks; therefore, they argue, the deportation and massacre of the Armenians were only a lawful and natural act of self-defense by the Turkish population.

In the 1930s, the Armenian Question and the Armenian Genocide were not discussed by international diplomacy, and Turkish historiography showed interest in this problem only in terms of falsifying the entire history of the Armenian people. Turkish historiography returned to the Armenian Question in the second half of the 1960s, when the 50th anniversary of the Great Tragedy of the Armenian people was widely commemorated around the world. A little later, the actions of the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) – targeting Turkish officials – again reminded world public opinion of the Armenian Question, the Armenian Genocide committed by Turkey’s rulers, and the impunity for that crime. In the anti-Armenian campaign that unfolded in Turkey, not only historians but also politicians, diplomats, and journalists took part, flooding domestic and foreign markets with low-quality publications on Armenian topics; a significant percentage of these were published in European languages. Turkish historiography of that period underwent no conceptual changes, but the striving to deny the fact of genocide and to minimize the number of Armenian victims became more explicit. The works of this period essentially repeat the assertions formulated in publications of the late 1910s and early 1920s.

The main theses of the Turkish historiographical concept of the Armenian Question and Genocide boil down to the following: since the founding of the Turkish state (15th century), Armenians lived together with Turks in peace, tranquility, and prosperity under the protection of Islam; the Armenians had every opportunity for economic flourishing; they served the Turkish state loyally. This view is advanced by all Turkish authors without

exception. The Armenians obtained very broad privileges and rights during the Tanzimat reforms in the 19th century – including a National Constitution, a National Assembly, schools, and wide opportunities for economic, cultural, and spiritual progress. All this, the Turks claim, the Armenians owed to their loyalty to the Turkish state. This point of view is developed by historians such as Esat Uras (“The Armenians in History and the Armenian Question”), Sadi Koçaş (“The Armenians Through History and Turkish-Armenian Relations”), as well as by the authors of a collection of articles titled “The Armenians.”

Turkish historians assert that, starting in the 1870s, under the influence of Russian and British intrigues, the Armenians began activities against their “benefactors” – the Turks – and formed various committees and organizations whose activities were directed against the Turks. The Armenians allegedly aimed to partition and destroy the Ottoman Empire. Mutual massacres ensued, for which the primary responsibility, they argue, lies with Russia, which was pursuing its own selfish political goals. This view is held by historians like Altay Deliorman (“Armenian Revolutionaries Against the Turks”), Cemal Anadol (“The Armenian File”), and Alper Gülener (“At the Origins of Armenian Terrorism”).

By crudely falsifying historical facts and events, Turkish historians, first, accuse the Armenians of terrorism, and second, claim that both Sultan Abdul Hamid and the leaders of the Committee of Union and Progress treated the Armenian “terrorists” magnanimously. Even after Armenians seized the Ottoman Bank in Istanbul, and after the Adana events (for which, of course, Armenians are blamed), the government forgave them and even punished some Turkish officials. But at the start of World War I, the historians contend, the Armenians refused to fight on Turkey’s side, struck at the Turkish army’s rear, organized armed uprisings in Van, Sasun, Shabin-Garahisar and elsewhere, creating a mortal threat to the empire’s existence. In such a situation, they argue, the government was forced to adopt a special law on the deportation of the Armenian population from the border vilayets. It is acknowledged that during the relocation “unfortunate incidents” occurred: the Muslim population hostile to Armenians resorted to extreme actions; moreover, Armenians also perished from hunger and epidemics. Three hundred thousand Armenians died (some Turkish authors put this figure as high as 600,000), but – they insist – the government was not at fault; it took all measures to prevent such “excesses.” Furthermore, they argue that as many (if not more) Turks died due to the same reasons. Therefore, the events cannot in any way be qualified as a massacre, let alone as a genocide of the Armenians. This view is defended by the majority of Turkish historians, though some place particular emphasis on alleged “atrocities committed by Armenians,” striving to counterpose an imagined “genocide of the Turks” to the Armenian Genocide. Among these authors are Mehmet Hocaoglu (“Archival Documents on the Atrocities of Armenians through History”) and F. Kırzıoğlu (“The Armenian Atrocities in the Kars Province and Around”).

Turkish historians persistently seek to justify and rationalize the necessity of the deportation of the Armenian population. Salahî Sonyel (“The Armenians in History and the Armenian Question”), Abdullah Yaman (“The Armenian Question and Turkey”), and İbrahim Ozkaya (“The Armenian People and Attempts to Enslave the Turkish Nation”) draw parallels

with instances of forced resettlement or deportation of entire peoples in other countries, particularly the USSR under Stalin. A noticeable trend is a concerted effort to minimize the number of Armenians who perished during the deportations.

Turkish historiography’s campaign of falsification receives some support abroad, as noted earlier. Certain Western scholars, sometimes influenced by Ankara or by Cold War politics, have produced works echoing Turkish denialist theses. For example, Stanford Shaw’s and Justin McCarthy’s works questioned the intent behind the events of 1915 or downplayed the scale of the atrocities. These writings, often financed or promoted by Turkish governmental or affiliated institutions, have been used to reinforce Turkey’s narrative in international forums.

Nonetheless, critical voices in Turkey have also emerged. From the late 20th century onward, a few courageous Turkish scholars, journalists, and intellectuals began to challenge the official line. They pointed to the abundant evidence of centrally organized mass murder. Some, like Taner Akçam – often considered the first Turkish historian to acknowledge the Armenian Genocide – have utilized Ottoman archives to demonstrate the Young Turk regime’s intent to destroy the Armenians. This very limited opening of Turkish historiography has come at personal cost to those involved (legal prosecution, academic marginalization, or worse), but it marks a beginning of re-examining historical truth within Turkey.

In summary, Turkish historiography for decades systematically denied the Armenian Genocide, framing it as either non-existent or justified by Armenian treachery. This stance remains an official state policy. However, increasing pressure from international scholarship and a small number of domestic intellectuals is slowly eroding the absolute monopoly of the denialist narrative.

The Armenian Question entered international diplomacy after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. It refers to the issue of the protection and freedoms of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire and their struggle for liberation and self-determination. As described earlier, the Treaty of San Stefano (1878) first introduced an article (Article 16) addressing the condition of Armenians and obligating the Ottoman government to implement reforms in the Armenian provinces. This was further revised at the Congress of Berlin (1878) as Article 61 of the Berlin Treaty, which reiterated the promise of reforms under the monitoring of the Great Powers[37]. The period following the Berlin Treaty saw Great Power rivalry impede meaningful reform implementation, leaving the Armenian population increasingly vulnerable within the Ottoman Empire.

The failure of the Great Powers to ensure real reforms (and the substitution of Russia’s protection with vague international guarantees) meant that the Armenian Question became a tool of imperial diplomacy rather than a matter of genuine humanitarian

concern. The Berlin Congress marked a turning point: it internationalized the Armenian Question, but also sowed Armenian disillusionment with European diplomacy. Indeed, Armenian activists, seeing that European promises had not translated into tangible protections, turned increasingly inward, concluding that only armed struggle could secure the liberation of Western Armenia.

By the late 1870s and 1880s, Armenian revolutionary groups began to form, inspired by the idea that they could not rely on external intervention. The failure of the Berlin Treaty’s provisions (as the Ottoman Empire ignored calls for reform, and no power enforced them) provided impetus for Armenian national awakening. Armenian intellectuals and activists – including those in the Ottoman Empire and in the diaspora communities of the Caucasus – started organizing political parties and underground committees (such as the Hnchakian and Dashnaktsutyun parties founded in 1887 and 1890 respectively) with the goal of agitating for Armenian rights and, if necessary, preparing for self-defense or insurrection.

By the end of the 19th century, the Ottoman Empire was in deep crisis. Feudal structures were decaying, and all the empire’s internal antagonisms were sharpening. Ethnically, Turks made up only about a quarter of the empire’s population. They were the ruling nation, yet in terms of education and economic development they lagged behind many of the peoples they ruled. Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s regime became one of severe reaction – a period the Ottomans themselves called the “Zulüm” (Reign of Oppression). In the words of V. I. Lenin, the Ottoman Empire was “a rotting country”[38]. Abdul Hamid II brutally suppressed the national liberation movements of the empire’s Christian peoples. In the mid-1890s, the Armenian people also fell victim to these bloody repressions.

In the Armenian Question, the autocratic ruler saw a grave danger to the integrity of the Ottoman Empire. He had no intention of resolving it in the manner of the Bulgarian Question (through autonomy or independence), nor of granting Armenians any selfgovernment like that enjoyed by the Maronites of Lebanon. The Sultan aimed instead to deprive the Armenians of even the limited self-rule that their communities had traditionally exercised in religious and local matters. When creating new administrative districts (vilayets) in Western Armenia, the Ottoman authorities tried to partition the territory such that in none of the districts would Armenians constitute a majority of the population[39].

Considering the natural aspirations of the Western Armenians as externally incited “sedition,” Abdul Hamid directed the fanaticism of the reactionary elements of the Muslim population against the “giaours” (infidels). The forms and methods of terror characteristic of the Muslim feudal elite – barbarity, banditry, plunder – which had been used against Armenians in the Van and Erzurum provinces, now gained official state sanction with the creation of the Hamidiye regiments in the early 1890s. These were mounted units formed by Abdul Hamid II’s order, composed exclusively of Kurds and maintained at state expense. They were not part of the regular Ottoman army but constituted a separate

military force, based in the Armenian town of Erzinga (Erzincan). The main purpose of the Hamidiye was to organize Armenian massacres throughout the Ottoman Empire – a mission they carried out “brilliantly,” especially in 1894–1896. In 1895, the English author Walter Harris became convinced that the Hamidiye’s devastating raids formed the core of the Sultan’s deliberate domestic policy and aimed “to force the Armenians to leave their homeland”[40].

As the magazine The Spectator wrote, the Ottoman government feared the Armenians, taking into account their intelligence, bold and entrepreneurial spirit, as well as the fact that just across the Russian border (in the Caucasus) lived another million Armenians under Russian rule. In 1891, that journal warned that the Turkish authorities were preparing a mass terror against the Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire, with the aim of driving the Armenians into Russia[41].